Attic black figure vase painters transformed pottery into storytelling art of ancient Greece.

Key Highlights

Here’s a quick look at what we’ll cover in this exploration of Attic black figure vase painters:

- The black-figure technique involves painting silhouettes and then incising details.

- This Greek art form evolved through early, middle, high, and late phases.

- Painters like Exekias and the Amasis Painter are celebrated for their skill.

- Expert John Boardman helped classify the styles of many Attic vase artists.

- Each vase tells a story, from grand myths to quiet, human moments.

- These ancient artworks show the cultural and artistic values of their time.

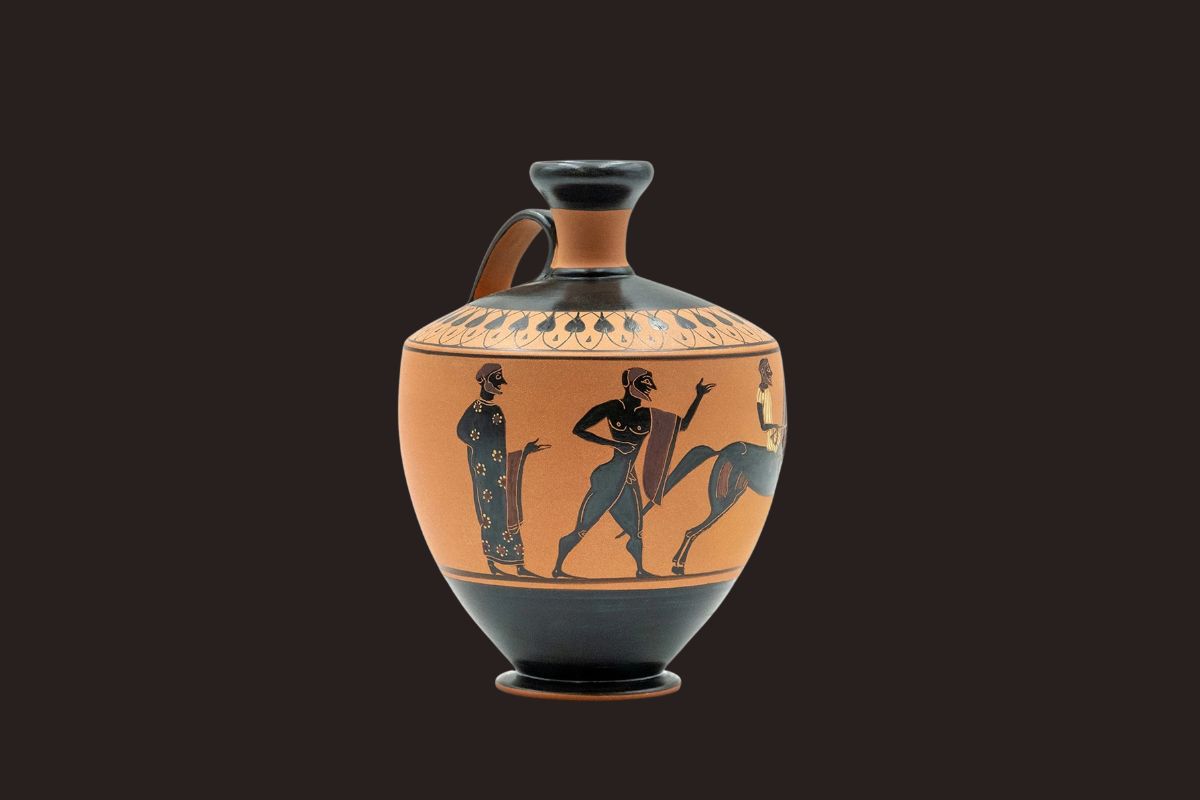

Have you ever thought about who made the bold black figures on old Greek vases? The attic black-figure vase gives us a way to see myths, heroes, and daily life from thousands of years ago. This style came from Athens and let artists put many stories on curved pottery. In this piece, we talk about the ways these artists made these works and share who some of the key Attic black figure vase painters in this attic vase and Greek style were.

Attic Black Figure Vase Painters and Styles

The attic black figure vase is a key part of ancient Greek art. Most of these vases be made from clay, just like many other ancient Greek pottery types. They show many patterns that tell stories about myths and daily life. John Boardman, a well-known art historian, points out how important these vases are for learning about old cultures. The dark figures stand out over the red base, which helps show the skill of the makers. You can find these vases in many digs. They teach us a lot about what people from that time did and what they believed.

Recognizing Signatures and Styles

Finding out which Attic Greek vase painter made a vase can be like solving a mystery, much like tracing the makers of famous Greek potters. Sometimes, the artist helps us out and signs the vase. For example, Exekias put his name on some of his vases, sometimes as the painter (égrapsen) and sometimes as the potter (epoíēsen). This gives you a direct link back to the workshop in ancient Greece.

But most vases do not have a name on them. So, people who study art, like J.D. Beazley, used a method called connoisseurship. This means looking at the style and small details in lots of Attic Greek vases. They look at things like the way lines are drawn or figures are shaped. By doing this, they can tell which artist or workshop made each vase.

If you want to spot different styles in attic vase paintings, check out these things:

- Composition: See how the figures are put together. Is the scene packed with people, or does it show just one moment or person?

- Incision Work: Look at the lines. Are they sharp and light, or thick and plain?

- Figure Proportions: Are the people drawn tall and thin, or short and strong-looking?

- Favorite Subjects: Does the painter often paint certain stories or scenes, like Herakles doing his famous tasks or people racing in chariots?

Early Phase (c. 590–570 BCE)

The early days of Attic black-figure painting were full of change. Artists began to leave old, simple shapes behind. They were starting to see what more stories they could tell with the new way to paint. At this time, large vases started to be covered with big stories from Greek myths, a feature often seen in geometric Greek pottery. This time made way for the best artists who came after. There are two painters we know by name. They are Sophilos and Kleitias. These two tried new things and worked to show even more on each vase. Their art shows us how Athenian artists were feeling better about what they could do, and that their skill was growing with every year.

Sophilos: the Earliest Attic Vase Painter Known by Name

Sophilos is known in art history because he is the first Attic vase painter whose name we know. He worked in the early sixth century BCE and was one of the first people to use vases for big stories. He signed his work, which shows that craftsmen in Athens were starting to feel proud about what they did. His main way of painting was filling vases with large, flowing lines of pictures. These showed big moments from Greek myths. Picture a band on the shoulder of the vase, with gods, heroes, and more. This helped make long stories, like a very old comic strip. Sophilos’s style was busy, with a lot of figures. It set things up for the focus on stories in Attic vase painting. Even if he was not as polished as the artists who came later, his work shows early hope that the black-figure style could be used for telling stories on vases in Greek art.

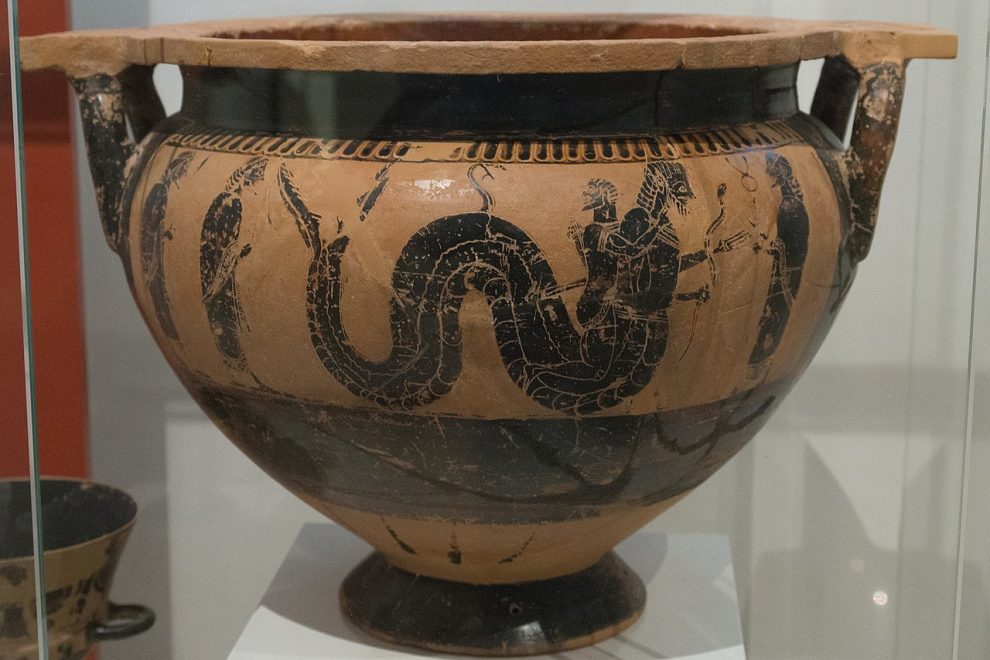

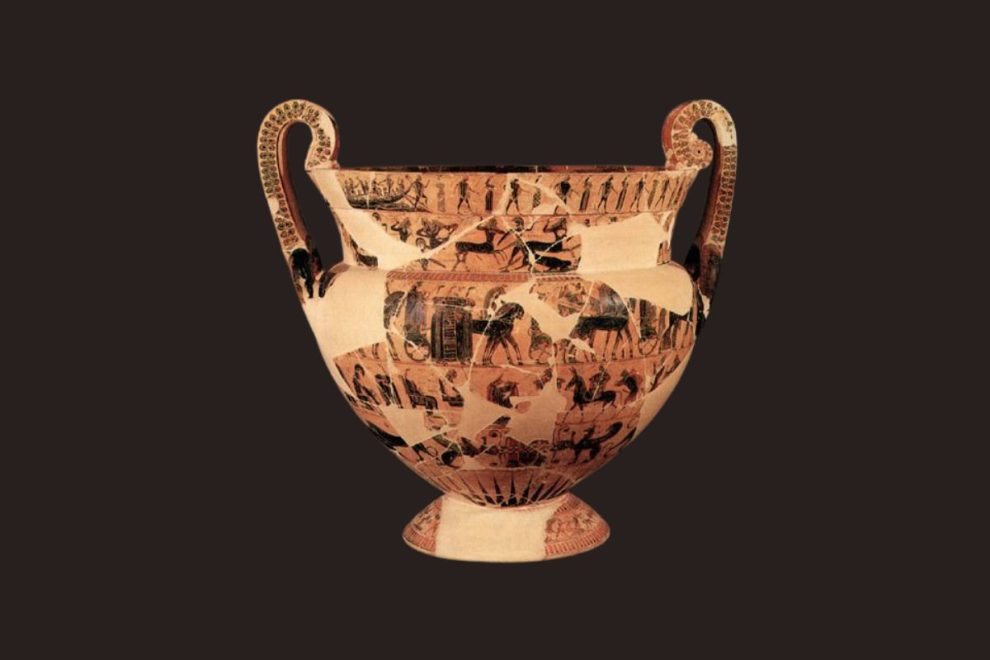

Kleitias: Creator of the François Vase

Kleitias, who lived at the same time as Sophilos, took pictures on vases to a new level, especially in monumental works like the amphora Greek vase. He worked with the potter Ergotimos to make the François Vase. This big vase is called a volute-krater, and people used it for mixing. The François Vase is one of the best early examples of black-figure painting. The François Vase has over 270 people and animals painted on it. These are put in wide, horizontal lines called registers. Each line shows a different story from Greek myths. Some of these stories are the Calydonian Boar Hunt, the funeral games for Patroclus, and the wedding of Peleus and Thetis. Kleitias took time to name many of the people, so there is no guesswork about the Greek stories on the vase. This vase is a key piece of old art. The hugeness of the scenes and tiny details show how hard Kleitias worked. He filled all of the vase with Greek myths, making the whole pot into a sort of myth encyclopedia. It shows us the highest skill seen in early mini painting style.

Middle Phase (c. 565–540 BCE)

When attic black-figure painting reached the middle stage, there was a big change in style. Artists stopped using crowded designs with many sections. They started to show just one strong scene in a big panel on the vase. This helped them show more feeling and made the design clearer. At this time, some of the best black-figure painters began to stand out. People like Lydos, Nearchos, and the well-known Amasis Painter made the attic vase art better. Their works showed simple lines, clear shapes, and new ideas.

Lydos: Major Figure Painter

Lydos was a leading artist in the middle years of Attic black-figure vase painting. The name Lydos means “the Lydian.” He ran a large and busy workshop, so he influenced many people. The style that he used is known for its lively look. You can see the strong and solid vases in his work. Unlike some other artists who often stuck to one thing, Lydos painted all sorts of vase shapes. The things you find on his attic vases are different too. He showed mythological fights, groups of gods, and scenes from daily life, themes also seen in ancient Greek vase painting. Being able to do all this made him important to his generation. Lydos signed two vases that have survived, and this shows his high status. There is a feeling of movement and action in what Lydos painted. He was very good at placing groups of people so the scene did not feel messy. There is energy and the shapes stand out. His vases use the black-figure style in a way that keeps the story interesting while each figure looks bold.

Nearchos: Considered an Early Influence on Exekias

Nearchos worked at the same time as Lydos. He was an important painter and potter who helped shape the black-figure style. He did not make as many works as some others, but the ones he did are known to be of very high quality. People say his works have great detail and clean lines. Nearchos signed his work as both the potter and the painter. This shows he was skilled at every part of making his art. Nearchos is remembered for the careful and fine lines he used. This set a new expectation for how exact people could be with their art. He liked to use a small space for his work. He often filled that space with many patterns and figures. You can see how he paid close attention to detail. It made every scene look special in its own way. He loved being precise and thinking about every part of his art. Some people who study art say he came before Exekias, a well-known artist for the high black-figure period. You can notice in Nearchos’s work how artists started to show more skill. This idea would later be seen even more in the art made by Exekias.

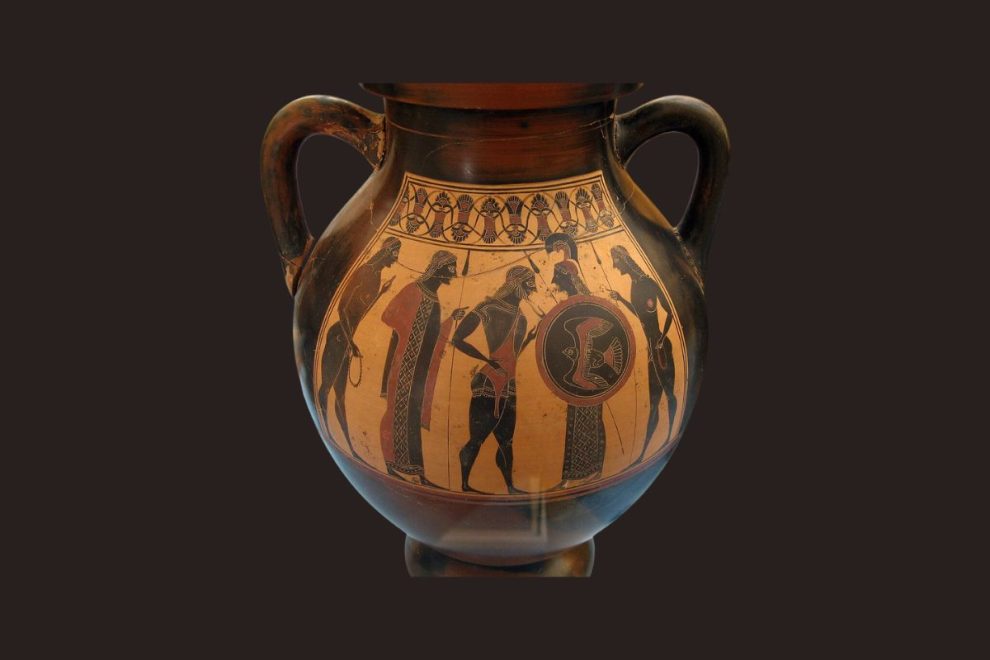

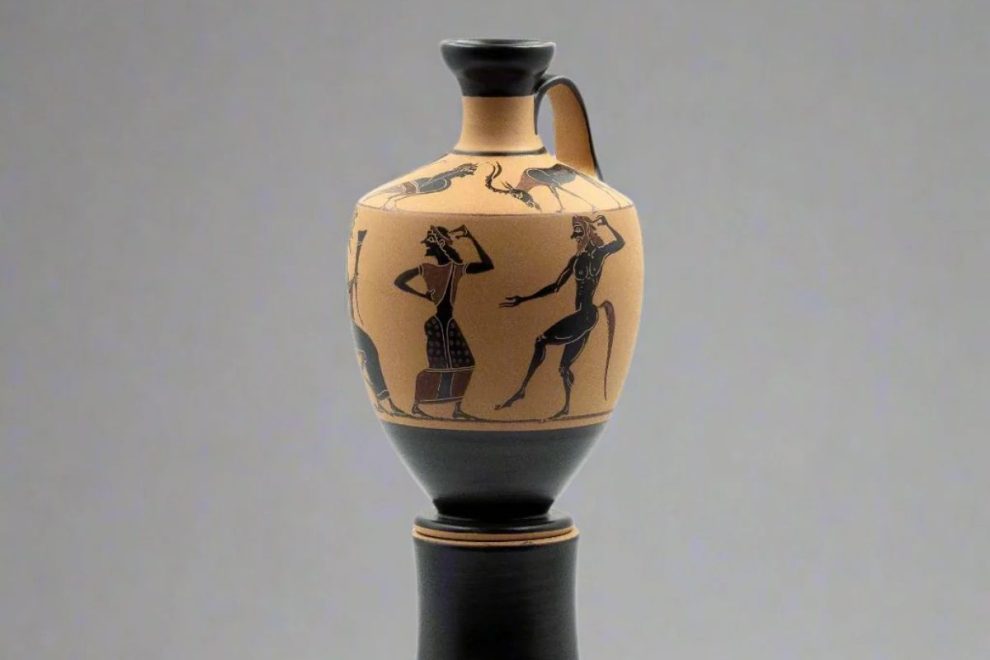

Amasis Painter: one of the Most Refined Black-Figure Painters

The Amasis Painter is known as one of the best and most graceful artists from the Archaic period, a time when black figure Greek pottery. His name comes from a potter named Amasis. Amasis signed eight pots that have this special style. Art historians saw these and have given more than 130 vases to the Amasis Painter’s hand. They can tell this by looking at the special way he made his art. The thing that makes the Amasis Painter’s work stand out is how neat and clear it looks. He often used smaller figures, but he always put them into full and well-ordered pictures. His artwork never looks busy or messy. When you look at scenes with Dionysus and his group or a wedding march, there is a nice balance. His art looks smooth, and this is different from what others of his time did. The Amasis Painter brought something new with the details he added. The way he drew patterns on clothes, the way hands move, and the neat lines all helped his art look pretty. This care for sharp detail and neat arranging is an important feature that makes attic black-figure painting stand out from other Greek styles of the time.

High phase (c. 545–520 BCE)

The high phase is the top point for Attic black-figure vase painting. At this time, artists made the technique better than ever before. They made vases that showed great skill and beauty. The designs on those vases turned more clever. Artists used deep cuts that stood out. The feelings in the pictures got stronger and clearer. This time is known for Exekias, who is seen as the best of all, and central to the history of Greek pottery. His vases show what high quality should look like. There were other artists, too, that helped shape this era. One is known as the Painter of Berlin. There was also a group called Group E. They all played a big part in making this a golden age for Attic vase painting.

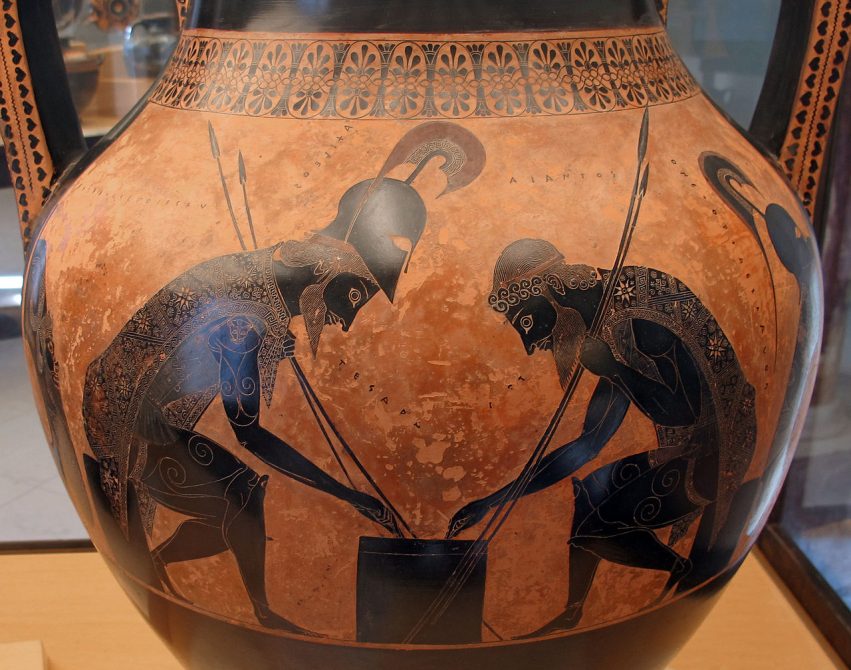

Exekias: Pinnacle of Attic Black-Figure

Exekias is known to be the best Attic black-figure artist. He worked between 545 and 530 BCE, and he was great at both making pots and painting them. Most people measure other black-figure painting against his work. John Boardman said, “The hallmark of his style is a near statuesque dignity which brings vase painting for the first time close to claiming a place as a major art.” You can see Exekias’s talent in his famous amphora, where Achilles and Ajax are playing a board game. Instead of showing battle, he chose to show a quiet and tense moment. The way he arranged the heroes, with their spears matching the vase’s curves, draws your attention to the game. Their cloaks and armor show lots of detail, made by fine cuts, and the result is stunning. What makes Exekias stand out is his skill in showing feelings. You see how focused both players are and feel the coming trouble of war. He used fresh ideas and skill to change vase painting into important art.

Painter of Berlin: Monumental Amphorae

The artist called the Painter of Berlin got his name from a big amphora that is now in the city’s museum. He lived at the same time as Exekias and is known for his powerful and large style, especially on big vases. While Exekias was good at making small, deep moments, the Painter of Berlin was great at showing big and bold scenes. His work often shows large and strong figures that fill up most of the space on the vase, a style that influenced later ancient Greek red figure pottery. He liked to use neck-amphorae because he could use the tall shape for his scenes. The figures in his art feel heavy and important, and his scenes are clear and bold, usually showing the main action from a myth story. The Painter of Berlin’s style shows how different artists could be during the time of high black-figure work. He wanted his vases to stand out and feel grand, which was different from others who focused more on small details. His vases were made to get attention, even from far away.

Group E: Associated with Exekias

So, what does Group E mean? The “E” comes from “Exekias.” This group got its name because these unknown painters helped Exekias grow as an artist. The art expert J.D. Beazley said Group E is “the soil from which the art of Exekias springs.” These artists worked with Exekias, sometimes right before or as he started his career. Group E matters because its members changed old ways of making pottery. They began to make new and simple vase shapes like the “Type A amphora.” This vase shape later became a regular style. They all showed a similar look in what they made, and they picked subjects in a steady way. The usual ideas in paintings from Group E included the birth of Athena, Theseus fighting the Minotaur, and Herakles with his labors, which is the most common scene. By giving us a strong pattern for their art, Group E set out a clear path that Exekias would later build on and move past. This makes them very important for the way black-figure painting changed over time, especially how people made vases.

Late Phase (c. 530–500 BCE)

The late phase of black-figure painting was a time when a lot of vases were made, but things were starting to change. Around this time, artists came up with the new red-figure style, and many people started to like it. Black-figure artists had to deal with this new style and work hard to stand out. Even with the push from red-figure painting, many groups still made great black-figure vases, including iconic attic pottery Artists like the Antimenes Painter and groups such as the Leagros Group made lively and well-done pieces. These works show the last strong moment of black-figure painting before most people switched to the newer red-figure method.

Antimenes Painter: Prolific

The Antimenes Painter was one of the top artists in the late black-figure period. This name comes from a kalos inscription on a vase in Leiden. He and the group working with him decorated hundreds of attic pots that still exist today. The work he did was steady and always good, showing us the reliable vase craftsmanship from that time. This painter liked to use some subjects and vase styles more than others. He is best known for showing myth stories on his vases, with many pictures of Herakles and his adventures. He also often drew Dionysus, who is the god of wine. A lot of his famous attic works are found on hydriae. The hydria is a jar used for carrying water. Its big shoulder was the right size for painting story scenes. The Antimenes Painter’s pictures may not have the new feel that Exekias’ work does, but he was skilled and thorough. His vases show what most late Attic black-figure painting looked like at this time.

Leagros Group: Last Great Black-Figure Workshop

The Leagros Group represents the last great surge of creative energy in the black-figure tradition. This large workshop, active around 520 to 500 BCE, is known for producing powerful and action-packed scenes on large vases. Their style is characterized by muscular figures, crowded compositions, and a focus on dramatic tension. Painters in the Leagros Group were masters of depicting dynamic mythological action. They filled their vases with scenes of heroes battling monsters, warriors charging into combat, and gods intervening in human affairs. Their work is full of energy and movement, a final, powerful statement for the black-figure technique.

Are there common themes found in Attic black-figure painting? Absolutely. Artists returned to certain stories again and again, though each painter offered a unique interpretation. Here are some of the most popular subjects:

| Theme Category | Example Scene |

|---|---|

| Heroic Myths | Herakles fighting the Nemean Lion |

| Trojan War | Achilles and Ajax playing a board game |

| Gods and Goddesses | The birth of Athena from the head of Zeus |

| Processions | Dionysus and his followers (maenads and satyrs) |

Acheloos Painter: Often Humorous or Grotesque Touches

The Acheloos Painter was one of the artists active in the late period of attic black-figure vase art. He got his name from a vase where Herakles is shown fighting the river god Acheloos, who could change into other shapes. This artist loves to show his own style with creative and sometimes unusual details. Most people making vases at that time liked to show big, strong, and serious scenes. But the Acheloos Painter did not mind adding little jokes or strange features to his pictures. The people he drew were lively and full of feeling, not stiff like in other attic vases. This way of painting shows that there was still a lot of variety in black-figure art at the end. The Acheloos Painter liked less famous myths and gave them his own touch. He was not afraid to use new ways to tell stories, even while working with the black-figure method.

Historical Importance of Attic Black Figure Vase Painting

Attic black-figure vase painting is very important. These attic vases show us a lot about Greek mythology and things people did every day. You can see scenes and stories from those times on the vases, which lets us know what Greek people thought and valued. Some stories shown on the vases are not found in their books, so this is the only way to see them. Also, these attic vases were a well-known export from Athens, found alongside Cypriot pottery and other Mediterranean wares. People found them from Italy to Egypt. This shows that many people liked Greek art. The trade in these vases helped share Greek culture and made Athens important in the world for art.

Impact on Ancient Greek Art Culture

The effect of Attic black-figure painting on ancient Greek art was big. It turned pottery from a simple skill into something people respected and admired. These works had deep art value. The pride of the artists showed in the signatures they left. Painters like Exekias and potters like Amasis wanted people to know the work was theirs.

Many Attic vases travelled to places outside Greece. This exchange influenced many, especially the Etruscans in Italy. Over 30,000 Greek vases have come to light there. People wanted these vases and this helped the Athens economy. It also spread Greek stories and attic art across the Mediterranean. Scholar Robin Osborne said that this demand shows how such items carried cultural ideas to other lands.

These vases also act as records that help us learn about the past. For example, scenes of Achilles fighting the amazon queen Penthesileia help us picture events from the lost poem Aithiopis. The greek painters were doing more than making pretty things. They told stories so people could remember their history for years to come.

Notable Collections and Where to View These Vases

After reading about the amazing attic vases and other works, you may want to see a Greek vase up close. You are in luck because these pieces have lasted many years, and you can find them in top museums around the world. Going to a museum collection is the best way to see how much skill there is in these Greek vases. Looking at a vase in person lets you see the fine lines made in the clay, the smooth shape of the vase, and the strong stories the artists tell in each design. Most of the vases talked about here are easy for people to visit.

Take a look at some of the top museums that have Greek vases on display:

- The British Museum, London: The museum has many Greek attic vases, including ones made by Exekias and the Amasis Painter.

- The Vatican Museums, Vatican City: You can see Exekias’s famous “Achilles and Ajax” attic vase there.

- The Louvre Museum, Paris: The museum has a large group of Greek vases and other old artwork.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Find different Greek vases here, some made by the Amasis Painter.

- Staatliche Antikensammlung, Munich: You can look at the popular “Dionysus Cup” created by Exekias.

If you want to know what these artists made, plan a visit to see an attic vase up close.

What Makes Attic Black Figure Vase Painting Different from Other Greek Styles?

Attic black-figure painting is special when you look at Greek vase art. While people first tried this way of painting in Corinth, the artists in Athens made it even better. They worked with the high-iron clay from their area. When this clay gets fired, it turns a strong orange-red. That color made the designs really stand out with the glossy black paint, much more than the light clay from Corinth. This look is what makes the attic vase style easy to spot. The way the artists cut details into the surface, showing shapes and clothing, was way more skillful in Athens than in places nearby.

The main different style is called red-figure. That one started in Athens about 530 BCE, inspiring later Attic red figure vase painters. It became so popular that it took the place of black-figure painting. The big change is in the colors. With red-figure, the background is black paint. People and shapes show in the natural red of the clay. Artists were able to paint details with a brush, which gave a smoother and more real look to bodies and clothes. But, the strong and bold look of black-figure shapes on attic vases gives them a big and important feel that red-figure never had.

Now, when you see a Greek vase, look for these signs to know which style it is. Both have their own look, but attic works are easy to spot because of their bright colors and sharp designs.

Parting Thoughts

The painters who made Attic black-figure vases were more than people who worked with their hands. They were real storytellers, using clay to capture what was special about their time. Kleitias told the big stories, while Exekias put deep feeling into his work. These Attic black figure vase painters show us ancient Greek myths and everyday life. Each vase is proof of how good they were and how clear their ideas were. The next time you see a Greek vase, look at the figures on it. Think of the workers, often not named, who made them feel alive.