Key Highlights

- Makron was a key painter of ancient Greek vases in the early 5th century BCE.

- His red-figure style is known for detailed figures and flowing drapery on Attic pottery.

- He had a long-term artistic partnership with the potter Hieron.

- Key works by Makron are found in museums like the Louvre and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- His pottery often shows scenes of daily life, myths like the story of Helen, and rituals.

- You can find his work by searching museum databases for “Makron” or “Hieron.”

If you’ve ever held a kylix in your hands (or even just seen one in a museum case), you know it wasn’t designed to be a “quiet” object. A cup gets lifted, tilted, passed around, and suddenly the painting appears, almost like a performance. That’s exactly where the Makron vase painter shines: he was one of Athens’ most accomplished red-figure cup painters in the early 5th century BCE, known for elegant figures, expressive gestures, and scenes that feel surprisingly alive.

In this article, you’ll learn who Makron was, why his partnership with the potter Hieron mattered, what details help you recognize Makron’s hand, and how to “read” a kylix, from the outer scenes to the inner tondo at the bottom of the bowl.

Makron ARV 467 126 komast – symposion (01)” by ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Who Was Makron Vase Painter?

Makron was active in Athens around 490–480 BCE, right at the late Archaic transition into the early Classical period, an era when Greek art starts to feel more fluid, more natural, more psychologically present.

What makes him especially important is volume and quality. Only one (or possibly two) signed examples survive, but scholars, most famously Sir John Beazley, attributed hundreds of vases to Makron based on style, making him one of the best-represented red-figure painters we can study today.

If you’re new to Greek pottery, here’s the simplest way to picture Makron’s world: these cups were made for the symposium, the social drinking party where conversation, music, flirtation, and storytelling all mixed together. Makron painted directly for that setting, so his images often feel social, intimate, and full of “human moments.”

Makron ARV 468 144 hetaira and youth – hetairai and youths (01)” — photo by ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

The Artistic Partnership with Potter Hieron

In Attic vase production, the potter shaped the vessel and fired it; the painter designed the imagery. Makron stands out because he didn’t bounce from workshop to workshop the way many painters did, he appears to have worked almost exclusively with the potter Hieron.

You’ll often see Hieron’s signature on cups associated with Makron (“Hieron made [me]”), and museum labels frequently reflect that division of labor: “Signed by Hieron as potter; attributed to Makron.”

Why does this matter for you as a reader (and a museum visitor)? Because once you learn to recognize that pairing, it becomes a shortcut to discovery. If you spot Hieron on a label, it’s worth slowing down and asking: Could this be Makron’s painting? In many cases, it is.

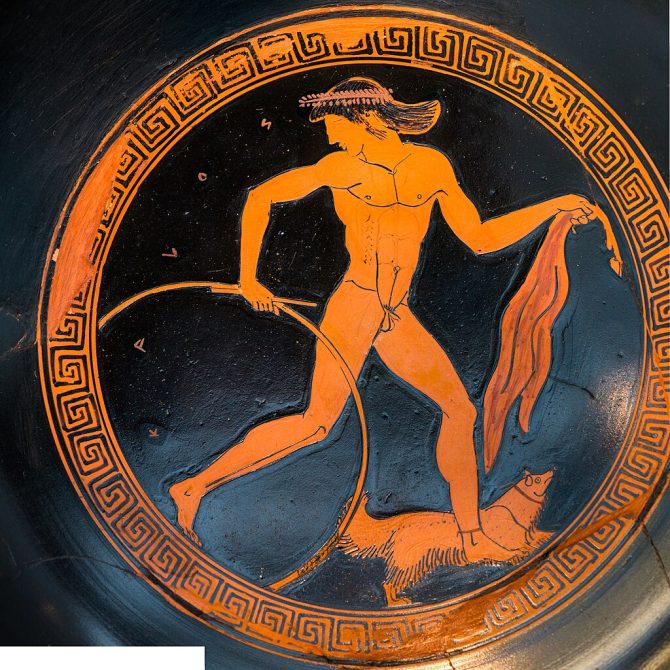

“Makron ARV 479 326 youth with fur and hoop running and dog 02” — photo by ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Hallmarks of Makron’s Red-Figure Style

Makron’s best cups have a kind of calm confidence. Even when the scene is busy, the figures don’t feel cramped—they breathe.

Here are a few recognizable traits to look for:

- Elegant linework and clear silhouettes: Figures read cleanly across the curved surface of a cup.

- Expressive gestures and storytelling: A turn of the head, the angle of a wrist, the way someone holds a cup, Makron uses small cues to make a scene feel specific rather than generic.

- Refined drapery: He’s especially admired for women’s clothing, how fabric falls, clings, and reveals the body underneath without ever needing to be explicit.

- Cup-first composition: Because he specialized in kylikes, he understood how people would physically encounter the images: the exterior is for across-the-room viewing; the interior tondo is the “reveal” at the bottom of the drink.

A quick “how to read it” tip:

When you look at a kylix, read it in three passes:

- Exterior Side A, then Side B (what others see while you hold it),

- the interior tondo (what you see as you drink),

- and finally the details, eyes, fingers, hems of garments, and the rhythm of spacing between figures. This is where Makron often feels most “Makron.”

Makron ARV 461 37 amazon – Dionysos with satyrs and maenads (03)” — photo by ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Notable Works and Where to See Them Today

Makron’s work is spread across major collections, which makes him surprisingly accessible, if you know what to search.

A few reliable starting points:

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York): multiple kylikes and fragments attributed to Makron, including examples dated ca. 490–480 BCE.

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: holdings include a kylix credited to Makron with Late Archaic dating.

- The British Museum (London): Makron has a dedicated biography entry, and the collection includes symposium-related cups and kylikes that help contextualize the world he painted.

- The Getty Museum: useful collection pages and artist profiles that summarize Makron’s activity and medium.

If you’re researching for a blog, exhibition text, or educational content, museum collection pages are gold because they often include short interpretive notes, like how Makron handles courtship scenes or how figures are named on the cup.

Spotlight: Kylix, with a Woman Sacrificing

One of the most rewarding Makron-type scenes is the quiet, ritual moment: a woman engaged in a libation or offering. These images can look simple at first, but they’re packed with meaning.

Here’s what to notice when you see a “woman sacrificing/libation” scene on a kylix:

- Gesture and focus: the careful tilt of a vessel, the controlled posture, ritual is shown as deliberate, not dramatic.

- Mood: instead of chaos, you get stillness; the scene feels private, almost respectful.

- Context: these weren’t “religious posters.” They were images circulating in social spaces, reminding viewers that ritual, order, and the gods were part of everyday life. (A number of museum collections catalog similar libation scenes on kylikes attributed to Makron or his circle.)

Makron ARV 468 144 hetaira and youth – hetairai and youths (02)” — photo by ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Themes Makron Painted

Makron didn’t paint only grand myths. In fact, he’s particularly known for scenes that sit close to lived experience: revelry, athletics, courtship, and symposium life, the kinds of situations his audience would recognize instantly.

That said, myth appears too, and when it does, it often feels “human-scaled,”. As if Makron brings heroic stories into a familiar visual language. The Met even notes cases where a mythological subject seems composed like a symposium scene. An approach that makes the myth feel closer, not distant.

Why did these themes matter? Because cups were social objects. They moved through hands, across conversations, through laughter and debate. Makron’s scenes weren’t just decoration, they were conversation starters, signals of identity, taste, education, and even humor.

Conclusion

Makron remains a standout because his cups do what great art always does: they make a distant world feel readable. His figures communicate through posture and glance. His drapery and spacing feel intentional and his partnership with Hieron gives us a remarkably consistent body of work to compare.

If you want an easy way to explore him further, go straight to museum databases and search: “kylix” & “attributed to Makron” (and also try “signed by Hieron”). You’ll start to see patterns. How Makron builds a scene around the curve of a cup, how he varies poses, and how a quiet interior tondo can feel as intentional as a full exterior narrative.

Featured image credit: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.