Key Highlights

- Euphronios was a key artist in ancient Greek pottery during the late 6th century BC.

- He was a leading member of the “Pioneer Group,” which helped move from black-figure to the innovative red-figure technique.

- His work is known for its detailed anatomy, dynamic movement, and powerful mythological scenes.

- The Euphronios Krater, showing the death of Sarpedon, is one of his most famous pieces of art.

- This krater became famous after it was looted and later returned to Italy from the Metropolitan Museum.

If you’ve ever fallen down a rabbit hole of ancient Greek vases, chances are you’ve bumped into Euphronios pottery, and for good reason. Euphronios was one of the standout Athenian artists working at the end of the 6th century BCE, right when vase painting was shifting from the older black-figure style to the newer (and far more flexible) red-figure technique. That transition wasn’t just a “new look.” It changed what artists could do with the human body, movement, and storytelling on clay, and Euphronios became one of the key names associated with that leap.

Image by: © Michael Greenhalgh

Euphronios Pottery at a Glance

At its simplest, Euphronios pottery refers to the vessels painted (and sometimes also potted) by Euphronios in Athens during the late 6th and early 5th centuries BCE, work that helped define early red-figure at its most ambitious.

Who was Euphronios?

Euphronios (often dated c. 535–after 470 BCE, or described as flourishing around 520–470 BCE) is known today as an ancient Greek vase painter and potter active in Athens. What makes him unusually “visible” for an artist so far back is that he actually signed a number of works, rare proof that these were celebrated makers, not anonymous decorators.

Why He’s Considered “Pioneer Group”

Modern scholars place Euphronios among the so-called Pioneer Group, a cluster of artists associated with the early rise of red-figure vase painting and a competitive, experimental approach, especially in anatomy, foreshortening, and lively scenes tied to elite social life.

Image by: Jastrow

Red-Figure Technique and the World of Athenian Workshops

Euphronios didn’t work in isolation. Athenian pottery was a workshop industry, artists, potters, and buyers shaping what got made, how it looked, and what subjects were in demand. Euphronios fits into that world as a maker whose style pushed what red-figure could do, while still serving real functions: drinking, mixing wine, gifting, and display at the symposium.

From Black-Figure to Red-Figure

Black-figure pottery “draws” figures in black slip and then incises details into them, effective, but limiting for subtle anatomy. Red-figure flips that: the background is filled in, leaving the figures the natural clay color, and details are painted on with a brush. That brushwork is the game-changer. It lets artists show softer transitions, more believable muscles, and a wider range of poses, exactly the space where Euphronios shines.

Shapes He Worked On

Two shapes matter a lot when you’re trying to understand Euphronios:

- Kraters (including the famous calyx-krater) were used to mix wine with water, big, social objects that invited large, dramatic scenes.

- Kylikes (drinking cups) played with surprise and intimacy: an image could appear inside the bowl as you drank, while the exterior told another story around it.

In other words, the vessel shape isn’t just “a container.” It controls how the viewer meets the image, up close in the hand, or across the room in a gathering.

Image by: © Michael Greenhalgh

How to Recognize Euphronios

If you’re trying to “spot” Euphronios pottery (or works attributed to him), think in terms of what he repeatedly does better, bolder, or more intentionally than many contemporaries.

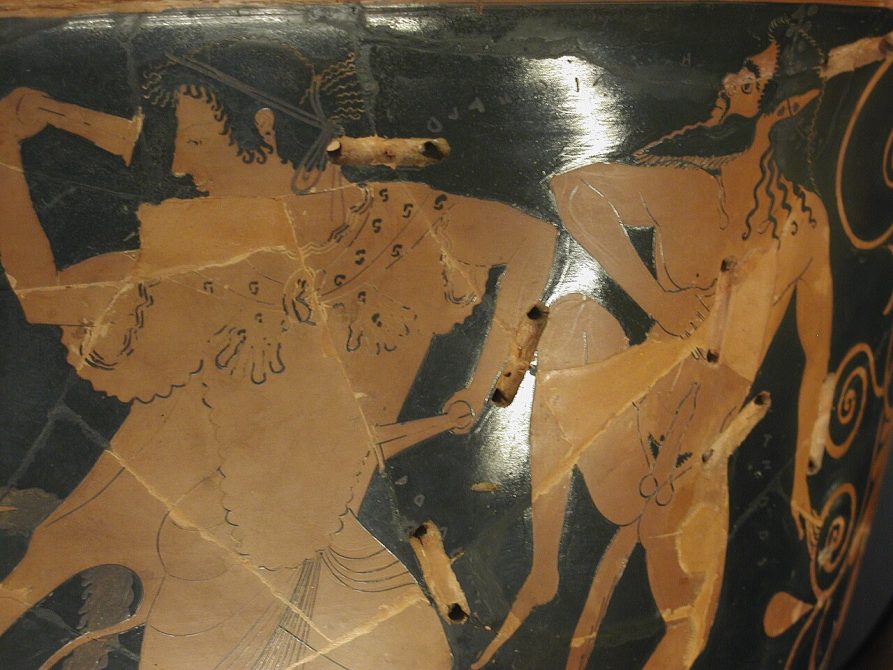

Anatomy, Movement, and Complex Poses

Euphronios is often discussed for his interest in the body in motion: torsos that twist, legs that carry weight, arms that strain, and poses that don’t feel like flat symbols. The Pioneer Group is especially associated with experiments in foreshortening and anatomy, trying to make painted bodies behave like real bodies.

Composition, Scale, and Inscriptions

Look for scenes that feel carefully staged: large figures, confident spacing, and compositions that lead your eye across the surface. Also keep an eye out for inscriptions (labels or signatures). They can guide the narrative, identify figures, or simply announce authorship, reminding you that these artists wanted recognition.

Image by: Jastrow

Signatures, Dating, and Attribution

A big part of writing about Euphronios pottery is being clear about how we know what we know, because not everything is signed, and museum labels often use careful language (“attributed to,” “manner of,” “circle of”).

“Egrapsen” vs “Epoiesen”

On Greek vases, you’ll often see two different kinds of signatures:

- egrapsen (“painted it”)

- epoiesen (“made it”)

These matter because they separate the painter’s role from the potter’s role. Though sometimes the same person could be involved in both. Britannica notes that Euphronios’ signature is identified on multiple vessels, including examples signed by him as painter and as potter.

How Scholars Attribute Unsigned Pottery

So what happens when there’s no signature? Scholars compare details: how eyes are drawn, how ankles turn, how drapery folds, how anatomy is structured, what subjects repeat, and how compositions “feel.” This tradition of careful comparison, often tied to long-standing cataloging approaches for vase painters, creates the “attributed to Euphronios” category you’ll see in museum databases.

Image by: © Michael Greenhalgh

Masterpieces and Iconography

When most people search “Euphronios pottery,” they’re usually thinking of a few headline works, especially one.

The Sarpedon Krater: What You’re Seeing

The most famous is the Sarpedon Krater (also called the Euphronios Krater), dated to around 515 BCE. It’s a red-figure calyx-krater showing the removal of Sarpedon’s body after battle. An image built for maximum emotional impact, with figures arranged to make the central body feel weighty and real. It’s also famously signed (Euxitheos as potter and Euphronios as painter).

Reverse Side and Symposium Context

What’s easy to forget is that this isn’t a museum poster first, it’s a functional object in a drinking culture where myth, status, performance, and conversation mix. A krater sits at the center of the symposium because it literally holds the mixed wine. So “serious” mythological scenes belong there: they’re talking points, mood-setters, and a kind of cultural flex.

Beyond Sarpedon: Heroes and Everyday Life

Euphronios pottery isn’t only about one masterpiece. Works connected to Euphronios also explore heroes (like Herakles in struggle scenes) and the rhythms of elite life, athletes, youths, and symposium moments. Subjects that fit the audience buying these vessels and the world they wanted reflected back at them.

Image by: Met Museum

Where to See Euphronios Pottery

Today, you meet Euphronios through museum cases and, just as often, through online collections. But the modern story of where these objects are, and how they got there, is part of the topic now.

Museums and Online Collections to Use

A strong way to research Euphronios pottery is to use museum databases strategically:

- Search by artist name (“Euphronios”), then filter by object type (krater, kylix), technique (red-figure), and date (late 6th–early 5th c. BCE).

- Read the provenance notes and the “attributed to” language closely. It tells you how confident the identification is and what scholarship supports it.

Major museum platforms (like the Met) also publish updates and context around high-profile objects and loans/returns. These can be useful for writing responsibly.

Looting, Restitution, and Changing Meaning

No honest discussion of Euphronios pottery can ignore cultural heritage debates. The Sarpedon Krater’s modern history includes a long dispute over provenance and its return from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to Italy in 2008. Followed later by display in Italy and relocation to a museum near where it had been taken. These moments change how we talk about the object: not just as art, but as evidence, property, and heritage.

Image by: Paris Musee

Parting Thoughts

The reason Euphronios pottery still matters isn’t only because the vases are beautiful (though they absolutely are). It’s because Euphronios sits at a hinge-point: when technique expanded, ambition rose with it, and painted bodies started to look like they could actually breathe, wrestle, grieve, or celebrate. At the same time, the modern journeys of these objects, especially famous pieces like the Sarpedon Krater, pull Euphronios into today’s conversations about looting, restitution, and what museums owe the cultures connected to what they display. In that sense, Euphronios remains doubly relevant. A technical innovator in antiquity, and a central name in how we think about cultural heritage now.

Feature Image by: Tim Pendemon